As Chair of Oxford Urban Wildlife Group for the last 5 years I have been privileged to be part of an amazing team of volunteers who are passionate about stewardship of a wonderful 3 acre nature reserve in the midst of East Oxford Boundary Brook Nature Reserve. The habitats in the reserve were created in the 1990's, when the group took over the lease, of what was once abandoned allotment land. The site is managed locally by this community group for the benefit of wildlife with a rich mosaic of habitats including high canopy woodland and hazel coppices, grassland, meadows and glades, with areas of scrub, 3 ponds and a marsh as well as a wet woodland, reed bed, wildlife garden and features such as a Bird Hide and a Forest School area. The nature reserve is run entirely by volunteers in the local community enabling people of all ages and background to get involved of the care of nature, to realise the importance of green corridors in the city and to act for nature in their own private gardens and other urban green spaces.

The atmosphere on the reserve is that of a wild place far from the city, in the summer under leaf cover the sound of nature close by is buzzing, the reserve teaming with invertebrates and birds, such as the brown hairstreak butterfly, jays and siskins, as well as being home to slow worms, bats, toads, small mammals, foxes and a wide range of other wildlife. Just yards from a busy road and yet this rich sense of the natural world draws those who visit to slow down, listen more deeply and get closer to nature and in doing so feel a part of it.

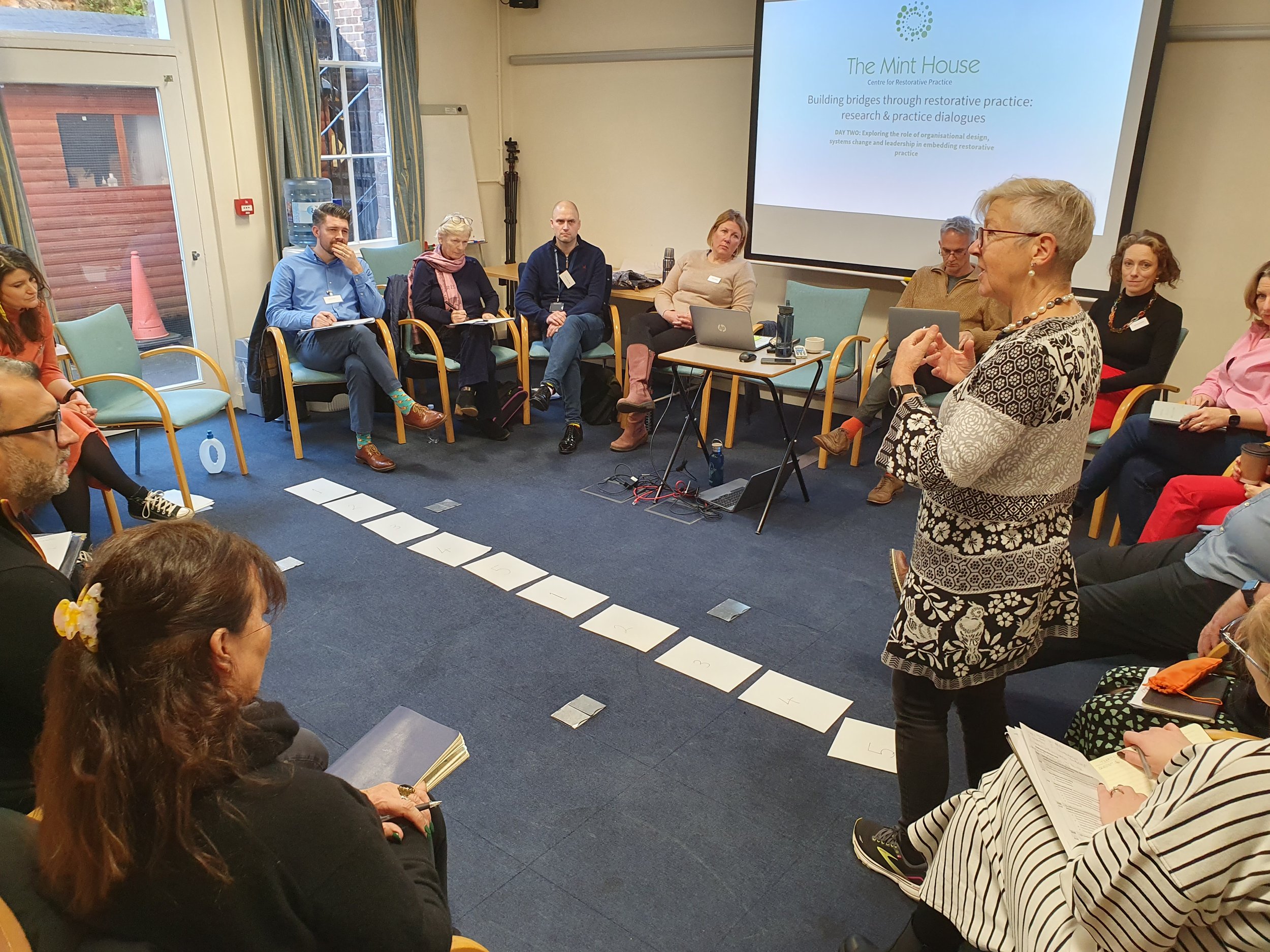

I was lucky enough to be invited to participate in a series of community research and practice dialogues looking at possible roles for ‘community’ in restorative justice practice, organised by The Mint House in Spring 2024. What arose for me was knowing I would like to extend community engagement in nature and in restorative practice through seeing how a listening circle might work with nature as the environment for listening.

With concern for ecology and the natural world being so figural at present a focus feelings relating to injustice to nature arose very clearly.

A few others who had attended the community dialogues were also interested and so we met and shared intentions and hopes in planning together a first listening circle to take place in the nature reserve. We named the event ‘Finding Common Ground’, set the date for 13th September 2024 and invited members of Oxford Urban Wildlife Group.

The invitation to the event said:

“Bring feelings of injustice with nature to a listening circle

Practice listening to each other

Discover ways of dealing with inner conflicts and polarising issues around the natural world

Build relationships within the community

Take away restorative tasks”

My intention was to create a space for deep listening together, to discover in more depth the feelings bringing participants together and how listening to each other might extend our capacity to listen to ourselves and others in nature in a listening circle together. I wondered how being in nature might shape new possibilities for myself and participants, whether we might hear and see ourselves in new ways, whether being outside in the interconnectedness of ecology might draw our minds and bodies into new places and what we might take away from our listening together.

10 of us met and took time to listen and arrive together sharing was bringing us to be there. As each sharing grew I felt new light and ease grow with the bird song and wildlife emerging around us, feeling a natural rhythm emerging in the sharing and spaces in between. The tension spoken about and sense of dis ease and inner conflicts by participants seemed to soften grounded by earth and aired and given space by sky as well as heard by the other humans. The expectations and judgements held deep within voices merged with the light breeze seeming to soothe raw emotion and enable more space for gentleness and acceptance. I was surprised by how safe I felt and could access and name ways in which I experienced myself in relation to nature with a clarity I hadn’t known before. Somehow I felt we became more aware of our scale as part of nature and possible more clarity around acceptance of that might be possible for each of us individually, accepting our difference and finding more balance in ourselves.

I began to feel how interconnected some of our feelings and concerns were as well as the uniqueness of each persons position. Around us nature had closed in. Insects coming closer, birds near by and a fox so close, we seemed so interconnected to the place he hardly noticed us. I felt our listening together was enabling a feeling of restoration for each of us and for our circle, and I experienced a strong sense of belonging, of shared endeavour and attunement in the natural landscape. I felt clearer about being seen and standing on my own ground, feeling more balance and able to voice my pledge to raise funds for a local fenland I wanted to support. I felt able to find my own small step and felt nature around me enable me to act for earth. I was glad to have met and discovered this enriched human field in the ecological field of nature and very curious around how this might develop and open doors to new awareness and understanding.

Reflections from a participant in the Restorative Justice in Nature meeting:

A curiosity and a desire to connect with others who care deeply about nature led me to accept the invitation to join in with a restorative justice for nature session at the reserve. I had no idea what to expect but I knew I was harbouring an inner angst about what I can actively do to help mitigate the harm caused by us humans to our wonderful natural world. An enduring injury prevents me from getting physically active and this compounds my sense of helplessness and feeling of ‘not doing my bit’ to help rebalance and restore our relationship with nature.

We sat out in the reserve deeply listening to each other with the birds singing around us, the sun warming our backs and a fox coming into view. We were being safely held in the space of this sanctuary. We had time to reflect, respond and ease into the peace around us.

I thought I might come away with a plan of what I can actively do, and my angst would dissolve. On reflection the ‘doing’ was not my starting point. Deepening my connection with nature is where I need to be. For me, the restorative justice for nature process has involved becoming less separate, more entwined, noticing more, being more awake, less in my head, listening deeply and responding to nature with all my senses. The angst has lessened and as I deepen my relationship with nature, I feel it transforming. I remain open and curious as to where the next restorative justice meeting in spring takes me!

- Debbie